Specialized hand protection covers a range of work environments.

by Dr. Marie O’Mahony

The specialty glove market is highly diverse, ranging from disposable products to ones that protect against extreme environments, or cuts and other trauma dangers. In addition to the technical challenges, which are to be expected, the market is increasingly dealing with issues of raw material access, price fluctuation and supply chains.

Nevertheless, it is a substantial world market, with the disposable glove market alone expected to be worth $14.87 billion by 2028, according to Grand View Research, with a CAGR of 9.2 percent from 2020. Other glove markets are anticipated to show similar percentages of growth providing a business incentive for fabric and glove manufacturers alike.

Supply challenges

“Recent record-setting long lead times, wide-scale shortages of critical basic materials, rising commodities prices and difficulties in transporting products are continuing to affect all segments of the manufacturing economy,” according to Timothy R. Fiore, chair of the Institute for Supply Management (ISM) Manufacturing Business Survey Committee.

Shield Scientific’s Nick Gardner illustrates this in pointing to disposable cleanroom gloves as being prone to the vagaries of COVID-19—specifically, the inadequate number of manufacturing facilities, the difficulty in recruiting a workforce and a global shortage of raw materials. The cost of acrylonitrile butadiene (nitrile) is one example, where prices have increased on average 10–20 percent each month over the past year with no sign of a downward trend. Gloves made with nitrile are commonly used in healthcare.

“Factories have responded by directing their focus on a massive scale to the thinner gauge and more basic gloves, which require less raw material and are correspondingly more profitable,” according to Gardner. “Unfortunately, the victim of these unfolding events has been speciality gloves for cleanrooms. It is a merciless war that is still being played out in the field of logistics with the increasing adoption of short-term contracts and lead times now extending to 600 days.”

The positive is that manufacturers have started to increase production capability in anticipation of the projected growth. Protective products supplier Ansell has announced a 50 percent increase in manufacturing capacity for beaded, non-latex surgical and sterile life sciences gloves. It is applying a multi-sourcing strategy for critical raw materials and using facilities in Sri Lanka and Malaysia—moves aimed at mitigating any future manufacturing and supply disruptions for the New Jersey-based company.

Preventing cut injuries

“In the United States, workplace injuries cost more than all cancers combined—an estimated $250 billion annually,” Joe Geng, vice president, Superior Glove Works writes in his book Rethinking Hand Safety. “The hand is the most commonly injured part of the upper body, with about 170,000 reported industrial hand injuries a year,” he says.

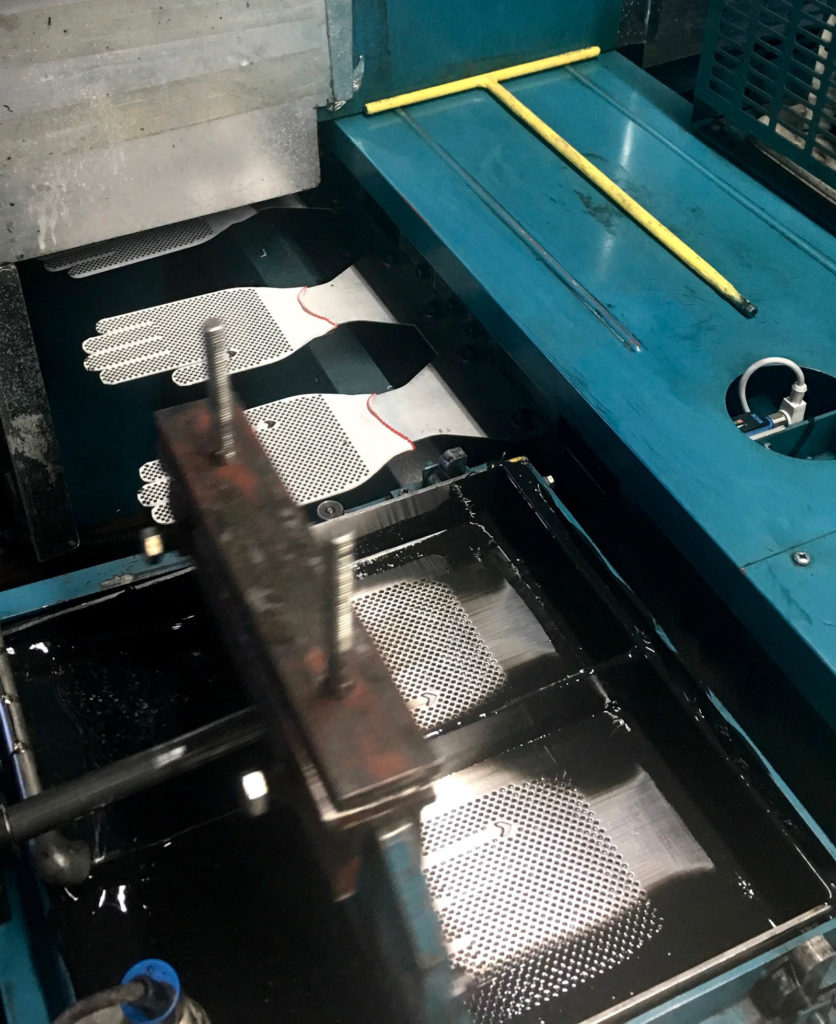

The Canadian company specializes in cut-resistant protective gloves for the work environment. Established for over a century, the company has proven itself to be consistently innovative with techniques. These include dip coating to produce touchscreen conductive finishes that ensure the coating itself is cut or puncture resistant, and better flexibility in the glove in extreme cold, when the wearer needs to perform tasks in temperatures as low as -50ºC.

While using high technology yarns such as Kevlar and Armortex for some time, the construction of the gloves and arm-protective sleeves has in contrast largely relied on hand skills. To meet the specific requirements needed to produce protective sleeves, Superior Gloves has designed and built their own robot in-house.

“Imagine a continuous, almost cut-proof knit tube that is maybe 1,000 feet long,” Tony Geng, company president says in describing arm protective sleeves, which is a growing market. “We have to cut all the sleeves to the proper length and sew the bottom and the top edges and put on the logos and cut thumb holes.”

Meeting orders that number in the hundreds of thousands each month, the company turned to robotics to manufacture more efficiently, using a carbide steel blade that “guillotines” the fabric. “Henry” the robot (named after Henry Ford) can now complete a sleeve in seconds. Having started with one robot in 2015 the company now uses four. To achieve greater efficiencies and quality control in the labor intensive sewing of elastic at the top and bottom of each sleeve, the company looked to the pantyhose and underwear industries, adapting machine technology to achieve a perfect tension every time.

Space challenges

As space exploration is taking on many forms, the future planning of apparel, including gloves, must take into account what is known, what can be imagined and even the unimaginable. The European Space Agency (ESA) has funded Pextex to imagine, identify, design and develop materials, including textiles, that could be used for future lunar mission space suits.

Rigorous testing is an essential part of the process so that the ESA has joined with pan-European partner organizations Comex in France, DITF in Germany and the Austria Space Forum (OeWF). The premise for future exploration is that humans will increasingly work in tandem with robots that scout ahead, prepare landing sites and go to places too dangerous or impracticable for humans.

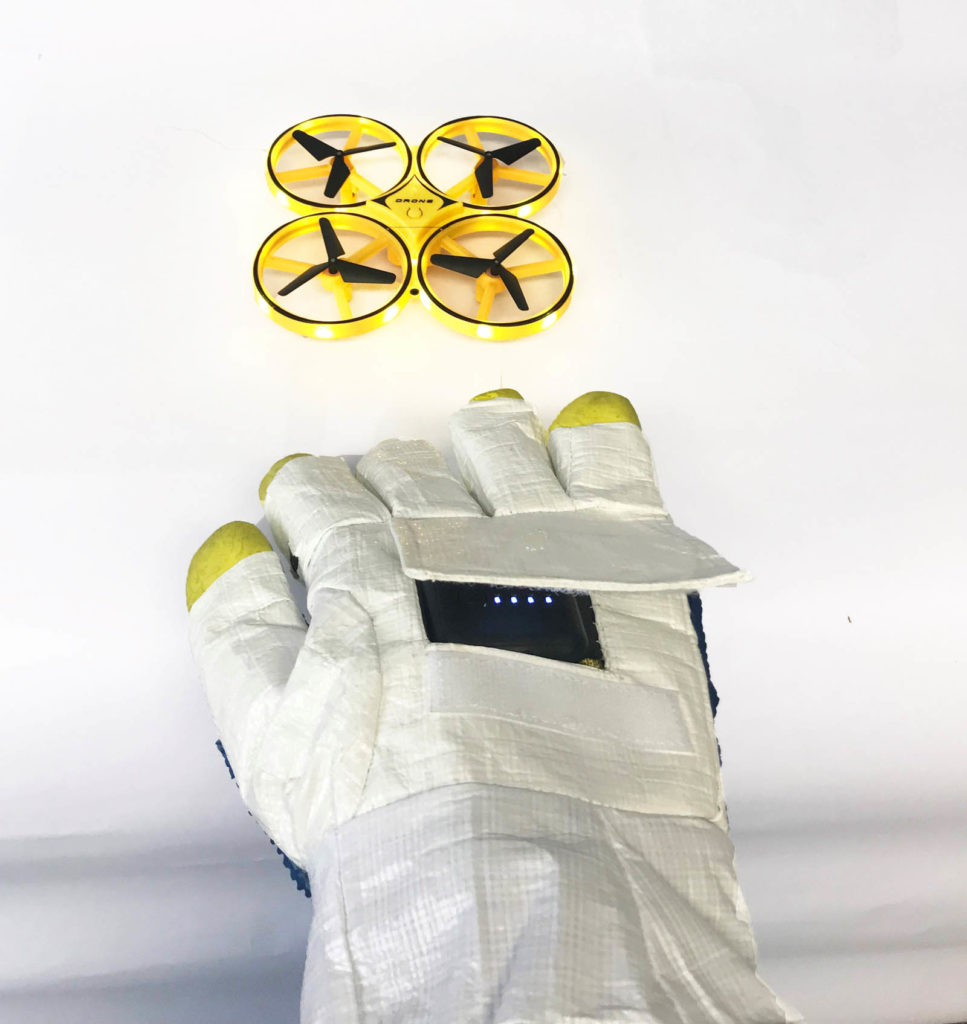

In one project Comex and designer Agatha Medioni have designed a prototype glove that addresses existing needs for protection as well as anticipated activities such as drone or lunar rover control using gesture alone. An integrated laser light is designed to measure distances or target objects while a display alerts the astronaut to the status of essential supplies such as oxygen levels. In the current spacesuit this display is located on the torso so that astronauts have to use a mirror located on their wrist in order to see it.

Humans have impacted the safety of animals, too, which was illustrated in a small exhibition (curated by the writer) for IFAI EXPO 2008. It included Canadian artist Bill Burns’ exhibit Safety Gear for Small Animals, a mini-museum that included nineteen scale model pieces, including gloves, designed to offer protection to small animals. The intricacy of the work served all as a reminder of the threat human activity poses to wildlife, beyond the environmental dangers facing humans.

Marie O’Mahony, Ph.D., is an industry consultant, author and academic. She the author of several books on advanced and smart textiles published by Thames and Hudson and Visiting Professor at the Royal College of Art (RCA), London.

Rethinking Hand Safety by Joe Geng, vice president, Superior Glove Works, is free to download on the company’s website.

TEXTILES.ORG

TEXTILES.ORG