Garment makers are using new technologies to optimize comfort.

With the growth of the wearable technology market, innovations in high-tech protective garments and a push by the U.S. military for more comfortable uniforms and gear, the issue of size and fit has also grown in importance. This is not a fashion or aesthetic choice, exclusively; it is a significant part of offering practical solutions for garments of all types—and for all shapes, sizes and genders.

The issue of the correct size and fit for clothing is so important that on at least one occasion it has led to the introduction of a new garment type in order to overcome poor size and fit. In her book, The Swimsuit, author Sarah Kennedy describes the invention of the playsuit in the 1940s as a response to women’s need to cover up ill-fitting swimsuits that had a tendency to sag when wet.

While the introduction of Lycra has made the swimsuit more flattering, the overall issue of size and fit persists. “A woman with a 32-inch bust would have worn a size 14 in Sears’1937 catalog; by 1967, she would have worn a size 8,” according to the New York Times (April 24, 2011). The good news is that change continues, made possible by technological advances and motivated by market and consumer demands.

The science of anthropometry

Size NorthAmerica from Human Solutions of North America is the first anthropometric survey to integrate both the United States and Canada to provide a representative survey of the North American population, and including both adults and children. The organization describes anthropometry as “the science that defines physical measurements of a person’s size, form and functional capacities.” While size and form have been addressed in previous size surveys, it is the acknowledgement and technical ability to measure subject’s “functional capacities” (or movement) that bring particular value to this approach.

The full body scan is undertaken either in stationary locations or in a fully equipped trailer that can be transported across the country. There are two components. The first is iSize, a web-based portal to house body dimensions and sizing analysis that can take up to one hundred measurements from each individual. It’s accompanied by an interview. The second aspect focuses on an anthropometric survey, bringing in more detailed data relating to body. The data can be integrated into CAD, 3D avatars or as physical fashion manikins. This scope and benefit goes beyond clothing to areas such as transportation and workplace design, where it can provide data to help improve safety, comfort and worker productivity.

Intimate apparel comes with some very specific challenges. Soft tissue is notoriously difficult to take measurements from. While many people will be comfortable having full body scans wearing their underwear, not so many women are keen to be scanned nude. The Hohenstein Institute, based in Germany, estimates that more than half of the female population are wearing bras that are ill fitting. They attribute this to a system of sizing that measures the difference between the circumference around and below the breast. This gives no indication of the shape or volume of the breast itself.

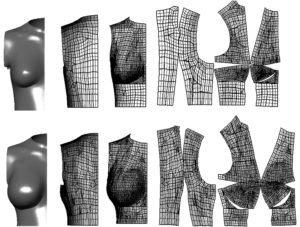

Researchers at the institute have now set up a project that will allow cup sizes to be determined taking account of both body shape and breast volume. They have taken data from approximately 12,000 women using 3D scanning technology. The age range goes from 18–80 years, with cup sizes that go from AA to J. What this has allowed is the development of virtual 3D models that are used for visualizing sizes and the creation of a more accurate 3D basic pattern that is based on volume.

Sportswear’s unique concerns

The sportswear industry has been looking for innovative and cost-effective solutions to size and fit. A global reach on the one hand means a bigger market for products, but it also brings a great diversity in body shapes and sizes.

Complexity increases further once the subtle differences between activities are taken into account. The muscle tone of the sprinter is very different from that of the marathon runner or Ironman competitor, as just one example. Collecting and collating data for different markets is costly, even with the advantages of technology. Brand diversity can bring great benefits in this respect as innovation can be shared across sectors.

Brad Cooper is senior director of product innovation at Fruit of the Loom where they use strategies such as tension mapping with the body in motion to gain a better understanding of where uncomfortable points in the garment are located.

“We can get individuals to walk and stretch, even ride a bike, so its very neat where the industry is going in helping to improve the function and fit of a garment on bodies in motion, not just static as it has been in the past,” Cooper says.

series of body maps and form a motion-led knit pattern, fundamentally shifting the conventional process used to make a typical T-shirt. Photo: NikeLab

Describing good fit as a core company belief, this culture allows innovative approaches to better fit to transfer across their bands such as Fruit of the Loom and Russell Athletic. More specifically, some of the ways that joints are supported in sportswear with compression fabrics can be seen to bleed over into developments in shapewear.

Cooper sees today’s tech-savy consumer as provoking innovation. “The technology curve for the consumer is getting shorter and shorter with mass adoption coming quicker than ever before,” he says. “So the challenge is, how do we take new materials and learn about them even quicker?”

This is an issue across many brands, including Nike. Kurt Parker, vice president of apparel design at the brand, describes how “in apparel design, we have forever been combining multiple materials, depending on the problem we are solving, often resulting in the build up of seams and complexity. Sometimes this creates a new problem as we are solving another.”

Rising labor costs coupled with advanced manufacturing and increasing anthropometric data are converging to reduce the number of materials needed. The NIKE A.A.E. 1.0 T-shirt is part of a new NikeLab collection titled NIKE Advanced Apparel Exploration (A.A.E.) 1.0. It uses computational design to merge a series of body maps (including cling, airflow, sweat and heat maps) to form a motion-led knit pattern.

The motion maps were considered in the context of how the body reacts in different environments—such as office, subway and streets—the intention being to reflect modern lifestyle as well as collecting a range of body map data. The design process brought together apparel designers with Flyknit engineers and computational designers described by the company as being “design-led, data-informed.” This is a reminder that technological advances in size and fit have to involve not just the consumer, but also engage the imagination of the designer in the process if we are to see meaningful change in how well our clothes and footwear fit.

Marie O’Mahony is an industry consultant, author and academic. She the author of several books on advanced and smart textiles published by Thames and Hudson and Visiting Professor at the Royal College of Art (RCA), London, and a regular contributor to Advanced Textiles Source.

TEXTILES.ORG

TEXTILES.ORG